I was born in 1941 in Nottingham, England. The first thing I can say is that life today is vastly different. It's not just technology, science, medicine, though they have changed significantly, but customs, culture, society itself, so I'll deal with this by subject area.

Daily Life

Back in the '40s, my dad walked about three miles to work and back again each day. Like many men, he worked in a factory. In his case, one that made lace and nylon. Most women stayed at home. At lunchtime he would come home, have his cooked dinner with us, and walk back to work. In the evening he'd return some time after six o'clock for his tea.

Every day, we had chores to do. If it were cold, or we needed hot water for a bath, I had to make a fire first thing in the morning. In those days, about a quarter of homes didn't have electricity. We did, but it was DC, later upgraded to AC. Many homes didn't have an indoor toilet. We were lucky. We had a bathroom and a separate toilet.

We were sent on errands to the shops, usually to fetch bread and vegetables, as we didn't have fridges and freezers. There were no supermarkets, so this meant visiting several shops. There was no self-service, either. You ordered at the counter and watched the shop assistant slice your bacon and so on.

We grew potatoes and rhubarb, but there wasn't much space for anything else. We would also have to shell peas from their pods, snap beans, peel potatoes, and slice carrots. All cooking was done from scratch using local produce.

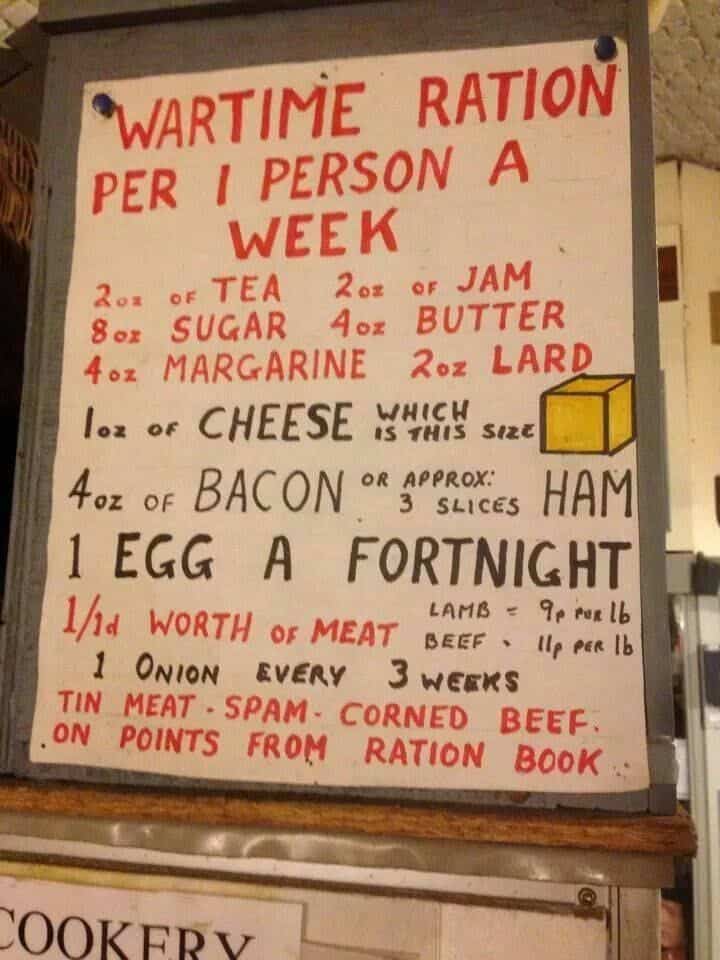

Because of the war we were on rations, which meant food was limited.

This amounted to:

It could be precarious:

Dad wasn't much of a drinker, but he did enjoy a quart of beer on occasions. He would send me to the hotel up the street with an empty bottle. They filled it up and I took it home, though occasionally I would stop to take a sip. If Dad noticed, he never said.

On Wednesdays, our mother would do the washing. This involved lighting a fire under a copper cauldron that was cemented into the corner of the scullery. She would fill it with water and when it was boiling throw in the bedsheets and other items she wasn't prepared to wash by hand. These were followed by washing powder and a small blue bag of something. I never discovered what that contained.

When she removed the washing, she fed it through a mangle like the one below that I was required to operate, to squeeze out the excess water, before we carried it outside to hang on the washing line.

The pantry was a cabinet with a drop-down middle section. A bowl of sliced cucumber and onion in vinegar could always be found there, sitting next to packets of butter and lard. Milk was kept cool in a bucket of water. Oftentimes, a muslin bag of sour milk hung next to the sink to become cottage cheese, which Dad loved. He was also fond of camomile tea. Ordinary tea was served from a teapot in a knitted cover. Coffee was made from a bottle of chicory essence.

Floor covering was linoleum. Few homes had fitted carpets.

On Saturdays, if Notts County was playing at home, Dad went to the soccer match. We would meet him afterwards and stop off at Central Market to buy mussels and cockles for tea. Then we'd catch the number 44 trolley bus back home.

On Sunday mornings we had a fried breakfast (egg, bacon, really tasty pork sausages, and tomatoes). Lunch was a roast dinner, while tea was a large pork pie (from Pork Farms, Melton Mowbray, pork pie capital of the universe), pickled red cabbage, other pickles, and a few cakes.

If on a Saturday the weather was fine and not too cold, and there was no footy, we went for a long (sometimes very long) walk into the countryside. I was told that I was taken on those walks when I was only 18 months old and surprised my parents by how far I could walk. When it was blackberry season we'd gather the fruit into bags to take home to make apple and blackberry pie. It was delicious. Ones bought from the supermarket today are but a pale imitation.

Walking was our main way of getting around, as car ownership was limited to the well off, although Dad had a motorcycle with a sidecar. He managed to transport us all until we grew too big.

On Sunday evenings, we went into the "front" room to listen to records on a wind-up gramophone. It was the only day in the week that we used that room, as it had the best furniture and ornaments. We would listen to Nelson Eddy and Jeanette MacDonald, Richard Tauber, George Formby, and some classical orchestral pieces.

Once, occasionally twice, a week our mother would take us to the cinema. She was very keen on Doris Day and Esther Williams films. We kids enjoyed Laurel and Hardy and Abbott and Costello, as well as Westerns. Every performance was preceded with a newsreel, and after the last screening of the evening we stood while a recording of the National Anthem was played.

School

I remember our classrooms had central heating, basically pipes that ran along the walls. There were around 40 kids in a class, sitting at individual desks with lids and inkwells. We used pencils to write in jotters made of cheap paper, but for learning to write properly, i.e. cursively, we used pens with nibs that had to be dipped in the inkwells. Most of my early efforts involved ink blots, for which I would be reprimanded.

Discipline involved canes and straps.

Kids were often absent from school with one illness or another. There were hardly any vaccines available. One boy in my class had calipers on his legs following a bout of polio, while another had had meningitis which made physical movement slow and stiff. Chicken pox, rubella, scarlet fever, whooping cough, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and pleurisy were rife. Vaccines for these diseases, as well as polio, weren't provided until the fifties.

I remember a kid being allowed to sleep on a form at the back of the class because his home circumstances prevented him from getting a night's rest.

During the mid-morning break, we drank free school milk. As this was left outside, sometimes it was frozen in the middle of winter and going off in the summer heat.

Play

We had few toys. A spinning top, a whip and top, and marbles were usual. We'd get those at Xmas. One year I had a Meccano set. We played in the street, as there were few cars around. We received American magazines, such as Captain Marvel and Superman, which we traded among ourselves. We also received the British comics Beano and Dandy, and later on the Eagle comic on shiny paper.

Money

Pounds, shillings, and pence. Twelve pence to a shilling; twenty shillings to a pound.

Can you imagine our arithmetic lessons where we had to add two sums of money together. Try £5 8s 3d + £3 17s 11d.

Fashion

During the War, it was Utility clothing, which could be bought with ration coupons. That meant a standard appearance dominated. Men were limited to single-breasted suits, which they wore with a hat. Women could buy dresses that incorporated padded shoulders, a nipped-in waist, and hems to just below the knee. However, people also made do with what was available. Dresses and skirts made from curtains, even bedsheets, for example, because wool, silk, and nylon were highly regulated.

After the war and the end of rationing, the fashion industry found its feet again. Hem lengths made front page news, especially when miniskirts were introduced in the sixties. Men found themselves wearing drainpipe trousers and winklepicker shoes. In the seventies, it was disco and flared trousers.

I remember in the fifties becoming influenced by American fashion. The US forces were located all over Britain. An airfield at Tollerton, near Nottingham, was a USAF base. The airman would come into town dressed in baby blue jeans, colourful t-shirts, and windcheaters, and in some cases riding Harley-Davidson motorcycles. I emulated them as soon as I had enough money to do so (though not the Harley-Davidsons).

Music

The music we heard on the radio was mainly ballads and orchestral. It wasn't until the early fifties that we had more variety, courtesy of the rock 'n' roll craze that swept the world. A film called Blackboard Jungle featuring Bill Haley's Rock Around the Clock caused consternation when it played in cinemas, with kids dancing in the aisles.

It was an exciting time for my age group. It was the teenage era ("teenager" was an advertiser's invention). We experienced Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Buddy Holly, and many more.

We jive danced at the Palais, read Melody Maker and New Musical Express every week, and bought stacks of 78 and 45 rpm records.

Food

Meals were plain. No spices apart from pepper, English mustard, horseradish, and salt, accompanied by HP Sauce and maybe Heinz tomato sauce. Sunday lunch was a roast, sometimes with Brussel sprouts. Unlike elsewhere that had it with gravy, we ate Yorkshire pudding with jam as pudding. Midweek dinners could be tripe and onions (Dad's favourite, but we kids hated it), rabbit pie (until myxomatosis), fish and chips, cod in parsley sauce, stew, etc, followed by a rice, sago, semolina, or tapioca pudding, or a tart or steamed pudding with custard.

Technology

The transistor had yet to be invented. Electronics were valve-based. Television was in its infancy and office equipment amounted to a telephone. a teletype machine, and a wax cylinder recording device. This gradually changed in the fifties and by the sixties we had early computers, fax machines, and automated telephone exchanges.

Ethos

During and after the Second World War, there was a strong sense of community. Immediately preceding the war there had been considerable poverty. You would have been thankful to have a job. If you fell ill, the costs of medical care could be prohibitive. But during the war, everyone made sacrifices for the common good, so it was no surprise that when the war was over the returning forces were in no mood for repeating the pre-war conditions. Labour was voted into power with a socialist agenda. Public utilities were nationalised, a national insurance system introduced, and, most particularly, a national health system brought in.

As the years passed, the unions became emboldened without real constraint, and the public mood changed. There were too many strikes, alienating public opinion. Eventually, Thatcherism became the economic model and people were encouraged to be independent of the state.

Human nature doesn't change over generations. We generally want the same things. But attitudes change.

During the war we had good reason to be fearful. Bombing raids were frequent. We lived a mile or so from a munitions factory. Houses at the top of our street were reduced to rubble. When the air-raid siren went, we dashed to the concrete air-raid shelter at the bottom of our back yard. (After the war, my dad turned it into a chook house.)

The war in the East ended when the US dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. A fear of nuclear war developed soon after when the Russians also had nuclear weapons.

At the height of the Cold War in 1962, when Khruschev sent a fleet of ships carrying nuclear missiles to Cuba (in response to US nuclear missiles being stationed in Turkey) to break a US blockade around Cuba, the tension reached such a point that we expected a nuclear war to break out. The US was willing to launch a strike against Moscow if the USSR didn't remove the missiles from Cuba. Luckily, Khrushchev backed down and the rest of the world sighed with relief. (I discovered later that there had been a secret agreement with Russia that the US would remove its missiles from Turkey four months later if Russia pulled its missiles from Cuba. The US reneged on the deal.)

We don't have that kind of tension these days. However, following 9/11, an exaggerated fear of terrorism occupied governments and media. We were already used to terrorist attacks by the IRA, PLA, and similar organisations, so there was no need for all for the extra security measures that followed. (However, it provided an opportunity for those in authority to exercise more restraint on the population.) It wasn't a change of target that made people fearful. It was the relentless feeding of fear by the media. This exceeded anything in my experience during my youth.

There are many things we are grateful for today, especially for medical science and a significantly improved standard of living, but it has come with an unacceptably high price tag in environmental degradation. A combination of a huge population growth (eight billion today compared with two billion when I was at school) and uncontrolled CO2 growth due to greed has also endangered life for future generations.